by Liz Griffin

Bone Dry

319 N. 11th Street

Saturday and Sunday from 12pm-5, and by appointment.

through July 22nd

Closing Reception: July 22nd, 5-8pm

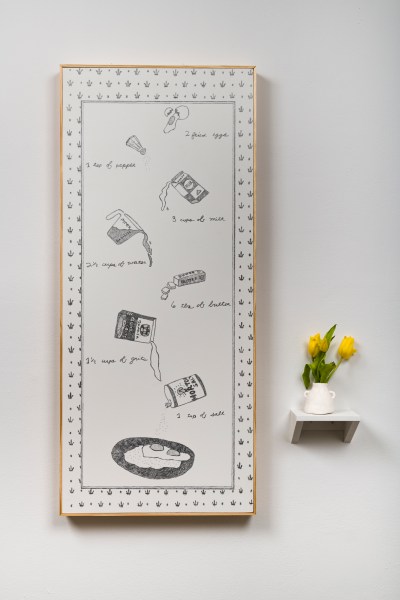

A pencil drawing on panel details the recipe for grits, while another evokes memories of conjugating verbs in foreign language classes. Pops of color from freshly cut flowers poke out of unglazed clay vessels resting delicately on wall-affixed shelves. From out of the corner, a large three-dimensional frescoed car faces its headlights towards the dry plaster forms and lightly-hued paintings — a car so large that its passage through the small doorway invites speculation. Stepping into Marginal Utility, greens and yellows reveal themselves from a wash of white, as do the tender moments and humorous gestures rife within Mariel Capanna and Lucia Thomé’s nuanced collaborative project. As one moves through the space, Bone Dry slowly discloses themes of loss, friendship, and the beauty of communities coming together to support, uplift, and nurture one another. I sat down with the artists to discuss these topics and more on the eve of their exhibition.

Liz Griffin: Could you talk a bit about how this collaborative project came about here at Marginal Utility?

Mariel Capanna: Yeah! Before Lucia and I were collaborators, we were friends. We went to PAFA for undergrad together, lived together for a year, went canoeing and fishing together once, and for a brief stint when I first moved back to Philadelphia from Los Angeles, we were coworkers at RAIR (Recycled Artist in Residency). So, the friendship has deep roots. I’ve shared breakfast with Lucia and I’ve had work meetings with Lucia, but this show was our first attempt at sharing meals and having meetings for the sake of a collaborative art project.

Lucia Thomé: And I’ve known David and Yuka [of Marginal Utility] for a while too. We’ve had some of their artists come through and do residencies and material-swaps at RAIR here and there. Really helpful Philly community friendship. They were stoked about our work and wanted to do a show.

MC: And when we proposed this show, we didn’t have a specific idea about what form our collaboration would take. The idea was just…

LT: …that they’d give us the space and time to make new works, which was really, really nice. And I think David and Yuka are really unique in that way, giving faith-based support, which ended up being really necessary. If we needed to commit to producing x, y or z many months in advance, we would be standing in a room of completely different, probably not as nice, artwork.

MC: Yeah. David and Yuka offered us the ability to figure out the show while it was happening, as we were making it. We pitched this thing as a collaborative show, not as a two-person show, which in retrospect was excitingly risky. David and Yuka didn’t know what a Lucia-and-Mariel collaboration would look like. Lucia and I didn’t know what a Lucia-and-Mariel collaboration would look like. I think people were surprised that it was a show of work we made together, rather than a show of our solo work sitting side-by-side.

LG: Are all the pieces collaborative? Or are there some pieces that you made individually while working alongside one another?

LT: Yes. Everything is collaborative. Within collaboration there is always going to be a question of who leads with what foot, but I think it’s just because of practicality. We actually just taped our heads together and did the whole show. [laughs]

MC: At our opening Lucia was describing it really well: that it was like a third person was making everything.

LT: People were so surprised by it! They really couldn’t tell who made what and so I just started saying ‘this other person, half-Mariel half-me, showed up to make the work,’ which feels like it could be true. Also sometimes we look a little similar, which makes it funnier.

LG: How did you both step out of your individual studios and come together to begin to form ideas for the show and the work? And the mindset that, okay, I’m not alone in my studio, it’s a tango now with another person?

MC: The most challenging part of this collaboration was the beginning. We have wildly different approaches to art-making and to communicating the ideas behind an artwork. We have different ways of getting started. I think the most difficult thing was, once we established that we would have a collaborative show, figuring out what to do in our studio meetings… we would have these meetings that ended up pretty much fruitless.

LG: Pen-and-paper, sit-down meetings?

LT: Oh yeah, like a real meeting. Writing things down, spilling coffee, maybe some doodling… it all started real slow.

MC: We weren’t getting anywhere because we were being so careful with each other. Like, there was a lot of “well, what do you want to do? We could maybe . . . but I don’t know, what do you want to do?” We did agree on a theme relatively early on, which we ended up kind of sticking to, but kind of straying away from. When we first named it, I pictured something really different than what we ended up with, and I think you did, too.

LT: Oh yeah. We were like, “we’re going to do a show about tombs!”

MC: And that made a lot of sense, because I had been making frescoes at the time and most of the frescoes made were inspired by or quoting from wall paintings in tombs. Also, I was thinking about funeral practices and burial practices. And then Lucia was excited about tombs and tomb-things from a sculptural angle, since there are so many weird, well made, charmingly poorly made, strange, funny objects associated with tombs. The material culture found in tombs. So, this theme was something that I could get really into for one set of reasons, and Lucia could get into for another set of reasons. I think that ended up being the easiest way for us to collaborate: by agreeing on source material and building mutual excitement about imagery and objects. We were conversationally shy with each other at our planning meetings, but then we got things going by sending each other images of wall paintings and urns and old family photos.

LT: There was some meandering for a while. But it was nice. Since we were working in my studio there were a lot of plaster-y, clay-ish type things that we could experiment with. We did some plaster casting onto glass and some plaster carving. Basically just messing around with materials next to each other. But like Mariel said, we really got going once we started committing to things that we agreed on or were both excited about. Like we decided that it would be nice if the whole show was mostly white. White clay, white plaster, very peaceful and light. Picking a tone for the work was a weird but good place to start. Communication flowed way better once we had agreed on that. And then actually, the first thing that we made that felt nice and we were both like “this is it!” was the show card.

Bone Dry, show card

MC: Yeah, that was a good moment. The image for the show card is one of Lucia’s sketchbook doodles collaged on a detail I found in the background of an old family photo. The image felt perfect when we landed on it . . . equal parts sensitive and playful. I think a lot of this show ended up being this odd attempt at playfulness and optimism during a deeply difficult time.

LT: You want to be humorous and playful, but you don’t want to be thoughtless.

MC: By this point I had realized that this show was in some part, for me, an opportunity to think about death and dying in a range of ways. To look toward historical examples of loss leading to the production of new things, sweet things, beautiful things. I was thinking about tombs and urns and sarcophagi, and then I discovered that Lucia had been secretly doodling cartoon ghosts in her sketchbook, which I thought was hilarious and kind of genius. Ghosts would never have occurred to me. I’d forgotten how light-hearted and spooky and funny the dead can be.

Good at Being Bad, fresco on panel, 2018

LT: Oh yeah, ghosts can be super silly. For sure there is some scary ghost imagery out there but I started looking for and collecting all the nice, cute ones. Casper didn’t make the cut in the final painting, he’s actually a little scary to draw since he has a nose, which is weird for a cartoon ghost. I think maybe at first I was a little embarrassed to suggest that we make something this silly into a fresco. Frescos were very intimidating to me before this show. Their historical context but also the process. You’ve got to commit to putting the pigment into the fresh plaster, first try. I wonder what Giotto would think if he watched me paint all those ghosts. Mariel made it easy to feel comfortable within the medium, she’s a fresco pro. One of the earlier ideas I pitched to her was to do a series of fresco signs. They were going to be Roman epitaphs or headstone inscriptions, in Latin, painted in cheesy vintage fonts. We nixed the idea, since it would have been too colorful and distracting but the idea of including Latin epitaphs stuck with us. And one word in particular from the epitaphs stuck with me, fui. It’s got a great shape. I did several pages of sketchbook drawings of the word before Mariel told me it means ‘I was’. So good.

To Be (The Verb), pencil on panel, 2018

MC: Lucia landed on the word fui, the perfect tense of the verb “to be” so: “I was, I have been” or, “I existed, I have existed.” The word does have such a good little shape, but we didn’t know exactly what to do with it. Then Lucia got excited about something she stumbled upon online, and sent me a screengrab of a Latin conjugation chart for the verb “to be.” Seeing it brought me back to high school Latin class, where I committed this chart to memory. Anyone who has learned a new language is probably familiar with the format of the six-row six-column verb conjugation chart. The rows across indicate the person, I am, you are, he or she is, plural and singular. The columns indicate the tense: present –I am, imperfect – I was being, future – I will be, perfect – I have been, pluperfect – I had been, and then finally, future-perfect – I will have been. So the chart references both the individual and the collective and, all at once, past, present, and future. While making this show, I discovered the chart as a comforting model for how to think about loss. It’s a big image in that way. That chart is something I expect to see on a worn and folded 3×5” flashcard. Here we’ve made it a monument.

Car (Tomb), fresco on foamboard and wood, 2018

LT: And the car, doing the car was a pretty easy thing for us to agree on. It was a ‘definitely, yes, must be in the show’ from early on.

LG: Yeah, how did you get this car here? I have to know.

MC: It was assembled in the gallery. Er, maybe I’m giving away a secret.

LT: It comes in pieces.

MC: I thought this was another cool part of collaboration, working with each other’s strengths. This fresco car was something that I could imagine, but could never imagine actually making. When the idea was floated like, ‘What if there was this big car?,” Lucia dove headfirst into figuring out how to fabricate it: how to make this plaster car light enough to carry, and how to fit it through small doors, how keep it cute all at once. I have next to no ability to do this kind of physical problem-solving.

LG: So the car is made from plaster? Foam?

Process shot of Car (Tomb)

LT: It’s both. If you did a cross section cut of it you’d see there’s a wood frame, foam sheets, stucco and then fresco plaster. We needed to fit in a teeny elevator and through a 34-inch doorway so it had to be modular. That was tricky. Seven pieces made the most sense. Some of the pieces, like the hood, the windshield and the trunk rest on the frame but the other pieces are bolted together. We had to patch the seams in the gallery but it’s pretty straightforward to take apart and put together. It was a good puzzle.

LG: Cars are very much like tombstones to me. They’re kind of ironic, in that the second you drive off the lot and drive away with it, money dies… and your car continues to depreciate with every mile you drive.

MC: That’s such an interesting point, I hadn’t thought of that. I was in a phase of really digging through family photos because my Dad died in January, so I found this amazing collection, this big box of old photos. It was comforting for me to look through all of them. I ended up finding an album of my birth parents on a road trip in France some time in the mid-’80s, and they were driving this white Renault 9.

LT: Is it 9 or 11?

MC: Somewhere in between, the 11 is the hatchback version, the 9 is sedan. We ended up making it more like the 9. Anyway… I love the way that photos look from the mid ‘80s. They’re kind of flat, and the colors have this certain saturation, and the photo doesn’t pretend at deep illusionistic space. This photo from the road trip was just a really nice flat image, and since the car was white and black it already kind of looked like a drawing. It was easy to translate into a pencil drawing, and then it turned into a clumsy little clay sculpture, and then into this big fresco car.

LG: Could you talk a little bit about deciding to fresco the car? And about your materials and techniques in general?

MC: With the car we were interested in using the medium of fresco as a symbolic from. The plaster used in fresco painting is a mixture of riverbed sand and slaked lime which is made from limestone. When limestone is heated and hydrated its chemical composition changes to become a putty: slaked lime. Then, when it’s applied to a wall or in this case, to a car-shaped foam structure, and is exposed to air, it returns to its original chemical composition. The material goes from stone, to putty, and back to stone again. Lucia and I were thinking a lot about the cyclical and transformative properties of the materials we used — and we didn’t use too many materials. Mostly clay and plaster. Clay is soft and malleable until it’s exposed to air, drying to reach the eponymous “bone dry” state when the clay is at its hardest, but also at its most fragile. The clay needs to be bone dry in order to go into the kiln. This transition from malleable to dry to fired resonated pretty deeply with us, especially since some of the first things we were looking at together were ceramic urns used to hold ashes, or cremated remains.

How to Hominy, pencil on panel 2018

LT: Also, grits…We were already planning to make a grits recipe drawing when we bumped into the fact that traditionally, grits were made with lime. Corn kernels were soaked in lime to produce meal that was then used to make grits. All of which was kind of funny, because that’s like how you make frescos.

LG: These are really interesting parallels. When I think about both of your works individually, I am thinking about landscape and movement with RAIR, cycles of trash, the cyclical nature of the readymade, and landscape within frescoes. Are there any parallels in this body of work to previous landscapes you two have utilized in the past? Or is this show more of a specific niche that you’ve both carved out for the work to exist right now?

MC: That’s true, I’m often thinking about landscape or, more specifically, about folk representations of American landscapes; looking toward the visual rhythms of particular places, urban and rural. But while I worked with Lucia to develop this show, we weren’t really engaging with those ideas. This show kind of derailed us both from our usual constellation of interests. The part of Bone Dry that might nod to the theme of urban density would be these little votive figures. The forms of the headless reclining figure and the headless standing figure are very loose quotations of Etruscan sarcophagus lids and Sumerian votive figures, respectively. In both cases hundreds have been unearthed, all almost identical. We were looking toward late Etruscan tombs which were often decorated with frescoes mimicking domestic interiors, or tree-lined outdoor sites for feasts, and the tombs would be filled from floor to ceiling with sarcophagi each topped with a lid shaped like a reclining figure. There’s a sweetness to this idea of the dead continuing to share meals and hang out with each other, after life. The figures look almost exactly the same, but with a delicately individualized face, or maybe holding something specific. These tombs offer a visual harmony between the individual and the collective, which can feel in conflict in a densely populated city. And then there are the daisies and the buttercups, the small flowers we associate with ground-cover in city parks, or in graveyards.

Votive and Lid, earthenware, 2018

Votive and Lid, earthenware, 2018

LT: And the way we hung the daisy and buttercup paintings in the show makes them feel more weightless to me. With the ground plane, bed of flowers, being behind the figures and the car- all tipped over. Like a dreamy nap in a field.

LG: Yes. I was thinking about land and cityscapes as well in relation to a show Lucia had a while ago about individuality and the loneliness of being in a city in the summer.

LT: Yeah cities can be super lonely. Sensory overload is real. For me, seeing the mountains of waste material at RAIR everyday or even being in this building filled to the brim with galleries and artworks, there’s too many shapes and noises and narratives to take in. It’s hard to focus in a city, which can be isolating. Producing the show was like a comforting respite for us, and I hope it comes across that way to other people. Like, slow down, breathe, take a moment with some daisies and spend some time looking at a willow tree.

MC: We both have a tendency to look out, out, out out. Lucia is at RAIR surrounded by mountains of trash and cute construction vehicles and charming tchotchkes . . . she finds a thing that she loves and then finds a way to personalize and replicate it. And I usually work from some combination of movies or slideshows, always working from observation, always looking, pulling, and collecting, which leads to all the business of shape and color in my paintings. This show was a first for both of us, pretty deliberately turning inward.

LG: This show is incredibly intimate. Just knowing now, after we’ve spoken more, that it wasn’t simply an artistic collaboration, but time full of so much emotion with the passing of a parent.

LT: That was definitely part of it. This show was also just a friendship activity. I’m pretty bad at being serious. My way of saying, “hey, what’s up bud, I care about you, I’m sad with you, let’s hang out,” was saying, “let’s do an art show!”

MC: That ended up being, to me, what the show was about. We had plans to do this show about tombs when it still seemed quite possible that my Dad was going to be around for at least a little while longer. I didn’t expect the timeline, exactly. He was sick, but there was still a lot of hope that things would get better. For him to die in January, basically the world stopped spinning for two months. I didn’t do anything. And then, to have to make this show in May…the only thing I was capable of thinking about in a deep way was loss.

But then it’s like, what does that mean for our collaborative show? Lucia and I are not the kind of friends who tend to speak in emotional detail about emotional things. But her company, her lightness. Sharing meals. Working on how to make slip for casting – it was really, really nice.

LT: We had a really nice routine. It was so wonderful.

LG: So you were able to step away from RAIR?

LT: I was. I feel lucky that my job is fairly flexible and we’re all generally supportive of each other’s individual artistic endeavors.

LG: So now you both return to your studio. Independently? Collaboratively?

MC: [Laughter] Lucia’s trying to set up our next collaboration.

LT: I’m hooked. It’s cool.

MC: I think it makes sense for us to keep working together! But I’m going to grad school. Trying not to take on too many projects. But collaboration makes a lot of sense, especially because we work so differently. We have very different strengths.

LT: We’re a good balance. Similar work ethic. There aren’t a lot of people that I can work with in this way.

LG: You need them to really engage.

LT: Oh, yeah. In an obsessive way. A willingness from the moment you wake up to just go for it and be focused and care about what you’re doing.

MC: Lucia is very good at taking breaks though. Old news for most, but I’m learning that breaks are good for productivity.

LT: You’ll run the week-long marathon.

MC: It makes me, actually, a much less effective person. I’ve developed some healthier habits during my residency at Lucia’s house.

LG: That’s amazing. It’s so communal.

MC: We’ll definitely work together again. But we’ll never make anything like this again, so our next collaboration is a mystery.

LT: Yeah. I mean, this is probably a finished body of work. It’s closed.

MC: It’s so attached to this time in our life and in our friendship.

LT: But everything is for sale. You can put that in the interview. [laughter]: I mean it’s a really nice thing because we’ve actually sold a few pieces, which is not typical of this building. We’ve sold pieces to friends! Good friends, peers, which is wonderful. I don’t know, that means so much to me.

MC: They’re stewards of the work. Until now, I’ve only had shows that function as a collection of individual artworks. I’ve never made an installation before. This is new to me; making an album rather than a series of singles. I’ve never made anything where the sum of the parts is actually more meaningful than the parts themselves. So, I don’t know, I’d imagine that out of context of the whole show, each piece loses a lot of meaning. I love the idea that people who have actually been in here, the people who have actually seen the show as a whole, if they take a fresco or a sculpture home, it might be a stand-in for the feeling of the whole space. The same way the votive figures were meant to be stand-ins for people.

Renault 11, earthenware with pencil, 2018

Renault 11, earthenware with pencil, 2018

LG: I love hearing that peers bought work and participated in an economy that we all watch one another play in. It must feel so warming.

MC: It is. This is a non sequitur, but I was looking at these flowers and it reminded me. Yuka told me that, apparently in Japanese culture, you never give someone in a hospital a live plant, because symbolically, it suggests that you’re rooted there. Like, that’s the place where you’re never going to leave. Instead, you give cut flowers because they can be taken back to your home. Yuka and David were asking me about the cut flowers in the show. The first round of fresh flowers were beginning to wilt, so they were curious…are you going to let them die in here? Or put new ones in? I was overwhelmed by the question because both make a different kind of sense. I wasn’t quite prepared to make that decision in the moment. I mean, people bring flowers, it’s a common tradition. Graveside flowers, you keep on bringing them back, bringing them back, bringing them back. You refresh them. It’s a kind of stewardship.

LG: Yes. It’s a really big connection with land, too. Being on the same ground. What did you guys decide?

LT: I’ve been changing them. We didn’t ever talk about it, actually. There’s just a silent understanding that it needs to be done.

Lucia Thomé is a Philadelphia-based sculptor, and is Director of Special Projects at RAIR, a non profit artist residency housed within a construction and demolition recycling center. At RAIR, Lucia works with artists and other organizations to create artworks, exhibitions and programing that challenge the perceptions of waste culture. She received her BFA from the University of Pennsylvania, and her Certificate at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), where she was the recipient of the Von Hess Memorial Scholarship and Travel Award. Thomé is a former member of the artist collective Traction Company. Her work has been exhibited extensively at local institutions including the Philadelphia International Airport, PAFA, The Woodmere Art Museum, FJORD, Little Berlin, and Vox Populi Gallery. Thomé has had solo shows at LMNL Gallery and Napoleon Gallery (both in Philadelphia, PA) and was selected to be a participating artist in Grizzly Grizzly’s 2017 Community Supported Art project.

Mariel Capanna lives and works in Philadelphia. Recent solo and two-person exhibitions include Little Stone, Open Home at Good Weather (North Little Rock, AR); Left at Gross McCleaf Gallery (Philadelphia, PA); and Con/Safos, a collaboration with artist Rafa Esparza at the Bowtie Project (Los Angeles, CA). She is the 2018 Haverford College VCAM Philadelphia Artist-in-Residence, a 2014 Independence Foundation Visual Arts Fellow, and the recipient of the 2012 Cresson Travel Scholarship. Capanna has attended residencies at Skowhegan School of Painting, Guapamacátaro Art and Ecology Residency, the Mountain School of Art, and the Tacony LAB. In August 2018, she will be Artist-in-Residence at Shandaken: Storm King. Capanna received her BFA and Certificate of Fine Art from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. She will attend the Yale School of Art in Fall 2018.

Liz Griffin is a painter, a senior at Moore College of Art & Design, and an intern at Icebox Project Space and Title Magazine.