by Meredith Sellers

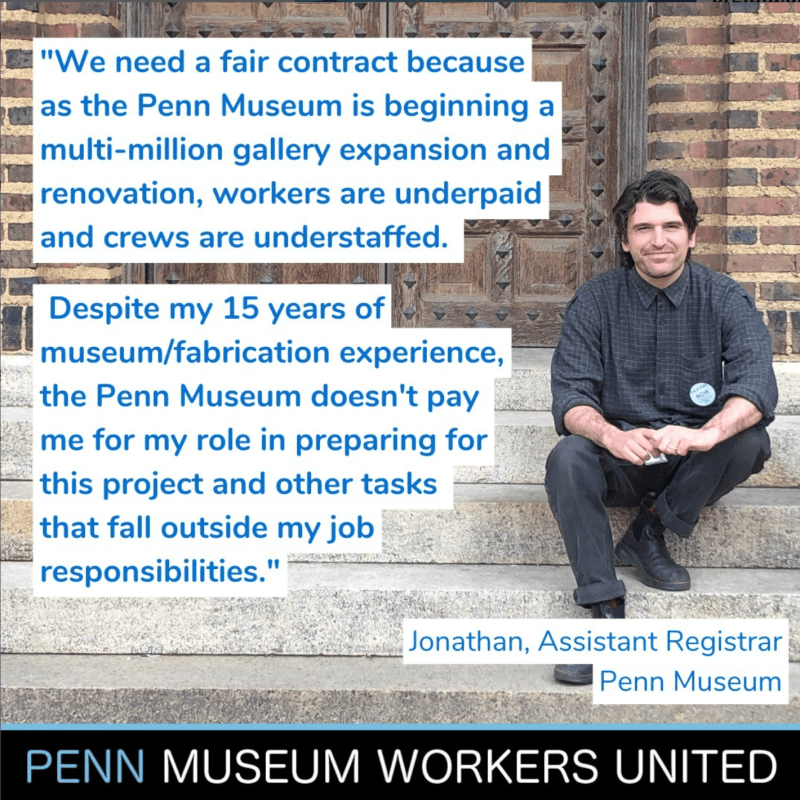

Penn Museum Workers United, the Penn Museum union, was officially formed in 2021 after over a year of organizing. Currently, they are in the process of fighting for a fair contract and are collecting signatures for a petition in support of their contract. Title editor Meredith Sellers spoke with union members Jessica Lubniewski and Emily Moore, who both work as Collections Coordinators in the Academic Engagement Department; Jonathan Santoro, who works as an Assistant Registrar; Matteo Hintz, the Project Mountmaker for the forthcoming Egypt and Nubia gallery; and Dan LoMastro, the Collections Digitization Assistant.

You can find Penn Museum Workers United on Instagram @pennmsueumworksunited and on Twitter at @PMWU397

Title Magazine: When did you all realize you needed a union, and how did you go about forming it?

Jessica Lubniewski: In January of 2020 a group of folks came together in a casual way to start the discussion around forming a union. At that time there was a lot of frustration at the museum about the power structure at the executive and middle management levels, lack of communication from the top and between departments, lack of accountability at the executive level, and low pay throughout the museum, among many other things. Organizing started amongst a small group of people, who spoke with a few different unions before deciding to join with AFSCME, who had recently helped workers to unionize at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Organizing a union involves talking to your coworkers, getting a sense for what they like and what they would improve about the workplace, and building solidarity through specific issues and hopes for a better workplace. Even in my short period of time employed at the museum before joining the organizing committee, it was clear to me that folks at the Penn Museum had A LOT of issues to organize around. I learned so much during my organizing conversations, especially when talking to the folks who have been working at the museum for decades—I learned that someone who had worked at the museum for over 25 years had recently retired at the paltry salary of $35,000/year. I learned that one of my coworkers was giving blood for money to afford their rent. I learned that the museum had fired multiple people without warning a few years prior and folks were escorted out of the museum by security without even being told why. Many coworkers talked about the ever-growing concerns about the unethical way the museum displayed and managed human remains. This became a topic of national controversy just a month before we went public with our campaign and seemed emblematic of the institutional disregard for equity and transparency we’d been organizing around. And of course, low pay, the high turnover rate, no reliable raises, and job insecurity came up in almost every single conversation.

Organizing primarily during the work-from-home portion of the pandemic was definitely difficult, but we managed to find ways to talk to all of our colleagues. With the support of our AFSCME DC 47 reps, we used the information we learned in our organizing conversations to measure the level of support for a union among eligible staff before filing for an election with the National Labor Relations Board and going public in May of 2021. We voted to form a union in August of 2021 and have been working on negotiating our contract with Penn and the Museum since October of that year.

Title: Who makes up your union, and what sort of tasks do they perform that are essential to how the Penn Museum operates? What makes you excited about working at Penn Museum despite some of the difficulties you’re grappling with?

Jonathan Santoro: Penn Museum Workers United is comprised of around 35 members who hold positions in Exhibits; Conservation; Visitor Services; Group Sales; the Business Office; the Cultural Heritage Center; Facility Rentals; the Gift Shop; Education; Marketing; Academic Engagement; Digital Resources, Archives and Publications; and the Registrar’s Department. We hold critical positions which are essential for visitor experience and the preservation of the University’s collection. More importantly, our positions strongly contribute to the Penn Museum’s mission of “making archaeology and anthropology accessible” since we facilitate classes, write grants, conduct gallery tours, perform gallery maintenance, intake visitors, construct display mounts and pedestals, install objects, input collection data, and ensure the safety and access of the museum’s collection. Despite monetary issues and a lack of clarity regarding job responsibilities, I love collaborating with my co-workers on large-scale exhibitions and smaller gallery rotations. As someone with a role that’s collections-based and performed primarily in storage areas or an office, it’s a moment that I feel I am able to communicate with museum visitors.

Dan LoMastro: Cultural institutions tend to attract people who are passionate about the media they work with and the Penn Museum is no exception. The people who work here want to be here because they love what they do. However, judging by the high turnover rate, it’s clear that loving what you do isn’t enough and that the Museum takes advantage of their employees’ passion by not offering competitive wages. Fair compensation for the work we do is something that’s absolutely necessary to retain hard-working professionals, and it’s been proven time and time again that higher pay equals happier workers, equals better quality of work. We like teaching, learning, research, working with the collections, interacting with communities, and being part of teams that tell stories to the world. We could do all of these things even better if we weren’t struggling to make ends meet every month.

Title: Why was it important for you all to unionize? Could you share some of the issues union members are struggling with?

Jessica: I’ve worked in many museums in 4 different states – California, Kentucky, New York, and Pennsylvania, and the issues that lead to unionization are universal – museums pay unlivable wages, employees are expected to pick up the work of unfilled positions without an increase in pay, there is high turnover, especially in the lowest paid departments. Workers are overworked, underpaid, and underappreciated. Despite hearing these concerns from their employees over and over, there is little incentive for museums to make the sweeping changes that workers are asking for. Why would they when it’s a point of pride to “do more with less?” And the Penn Museum is no different. Our union went public one month after the museum hired a new director, and they tried to convince us to vote no on the union and give him a chance to make the changes we were asking for without unionizing. So far I have yet to see any significant changes made that address the reasons we formed a union. Unionizing is the only way to make lasting, equitable change for workers in the museum, both at the Penn Museum and at museums throughout the country.

Emily Moore: Union members are struggling with a variety of issues, but some of the common threads are low pay, unsustainable working conditions, and lack of accountability. For a staff of passionate, qualified, and hard-working individuals we are grossly underpaid when examined against comparable academic museums, as well as similar positions elsewhere at the University of Pennsylvania. Working conditions for many individuals are strained when departments are severely understaffed for extended periods of time, resulting in staff not getting lunch or bathroom breaks, staff working far outside their job description without acknowledgement or compensation for this additional work, and eventually burnout. Such problems are not new and there is no accountability for letting them linger and worsen, despite years of employees asking for help. Since the University cannot hold itself accountable, the staff have turned to each other through unionization to create the changes we need.

Title: Penn Museum has had a number of major gallery renovations in recent years and is in the process of a $97.4 million renovation of the Egyptian galleries. How do these projects impact the work you do at the museum?

Jonathan: I work at the Penn Museum as an Assistant Registrar. Before deciding to take a job at the Penn Museum, I had close to 15 years of experience working various jobs that helped to preserve or create art, such as: Art Handler/Shipper, Object Conservator, Art Fabricator, and as a Part Time Lecturer teaching Foundations and advanced Sculpture courses. Registration work typically involves facilitating object access, processing acquisitions/deacquisitions, condition reporting and preparing objects for loans, and imputing lots of data entry. Due to lack of staffing and given my experience, I’ve been tasked to “help” with internal collection moves at the museum to prepare for the museum’s ambitious gallery expansion. For these projects, I primarily work alone to construct and dismantle pallet racking and shelves and to transfer collection objects that need to be relocated to make room for construction. My assistance with the Egypt/Nubia gallery expansion also includes building slat crates that house monumental architectural pieces that needed to be shipped to an offsite storage facility for conservation work. My job is no longer just a clerical position and has expanded to a massive amount of work that’s generally completed by a team of art handlers and a museum pack shop. Currently, the Penn Museum doesn’t employ art handlers or art packers and this work is absorbed by certain members of the collection staff, who also perform a host of other administrative tasks.

Matteo Hintz: I’ve been working at the Penn Museum for two months as of May. I was hired specifically for the Egypt project. This project is a massive undertaking, to a degree that I don’t think many people understand. Don’t get me wrong, I am beyond excited about landing this job. It is an opportunity that I had always hoped for to advance my career as a mountmaker/museum fabricator. However, as of now, over 2,000 objects need mounts made for them. A typical brass mount for, say, a football-sized object takes about 2 to 3 workdays to complete, on average. Many objects for this project are massive, and weigh hundreds of pounds. These objects will need steel armatures, which require considerably more time and physical exertion.

I knew what I was signing up for, but it is still my hope that the museum will be reasonable with the timeline for this project, and open to hire more help where it’s needed. Before coming here, I had worked at another prestigious museum as a mountmaker and their model was the same: operating with as small of a team as possible, knowing that these talented, high-performing employees are more than capable of getting the job done, yet working them to the bone with laughably low compensation for an excruciating amount of labor. It’s clear that they favor saving money over preserving the well-being of their people. I’m not feeling the heat yet, but I am feeling impending doom. I fear how this project will pan out due to the understaffing/lack of support in its beginning phases.

Title: Unions are cropping up all over, and especially at arts and cultural institutions. The cultural sector has long propagated liberal ideals, yet often lags behind in equitably compensating employees. What do you think the current proliferation of unions says about American culture in this moment?

Matteo: The popularity of Unions is a reflection of America’s growing class consciousness. Working people are realizing the worth of their time and labor. When discussing museums specifically, I think it’s part of the culture that employees are expected to be satisfied with the prospect of having a “cool job” that invokes passion and a feeling of being a part of something meaningful, therefore deeming it “worth it” despite low pay. But our economic predicaments are too dire to allow passion to overshadow our lack of compensation.

Jonathan: At many cultural institutions, there’s often a disconnect between the skills, belief, and dedication that the staff contributes and their pay. Many of the positions that are part of this bargaining unit require years of experience to attain them. As you might expect, the interview process favors a candidate with heavy credentials and hands-on experience. Despite this, many workers that are part of this bargaining unit take on side work to supplement their income. This hardship and sacrifice stands in stark contrast to the massive wealth hoarded by these institutions and the displayed opulence that’s a result of their Capital campaigns.

Within Philadelphia specifically, wages have remained stagnant and out-of-step for years now, despite aggressively rising living costs and inflation. This perhaps explains the surge that’s occurring locally, but echoing Matteo, I believe cultural workers are coming to realize that their time and labor has a value that should be family-sustaining.

Jessica: This problem in museums goes back as far as the founding of museums themselves. The first museums were privately funded institutions that were showrooms for rich men’s collections of curiosities that they gathered while traveling the world. “Working” in a museum was a leisure activity for rich folks and academics who traveled abroad and brought back chests of unethically acquired objects. Even into the 20th century, the work done in museums was often performed by the members of the families who funded museums and collections, and hence a fair wage was never an issue. Museums have also traditionally depended on volunteer work, again a leisure activity often performed by retired folks who choose to work without pay.

But in the past 30 or so years, the museum field has become very professionalized, where even the most entry-level jobs often require specialized degrees. There has been an explosion of Museum Studies Programs in the United States in just the past 10 years, both at the undergrad and graduate level, and this means that people are coming into the field with specialized knowledge and often a fair amount of student loan debt, yet the wages offered at museums have stagnated because for hundreds of years, they never had to pay wages. When folks are coming into the field with a Masters degree in Museum Studies that cost $60,000 and their starting pay is $18.50 an hour in a major metropolitan area, it’s only a matter of time before those folks either see the need for a union or move on to a different field. I’m one of the few people from my museum studies master’s program who still works in a museum. Everyone else has moved on to fields that pay more because, as the saying goes, we cannot eat prestige.

Title: What does the union hope to accomplish, and how will the union continue to support workers after you’ve won a contract?

Matteo: Our main goal is to ensure that our coworkers can live comfortably, and to continually hold the museum accountable for years to come, to ensure that we’re being treated fairly. Overall, with the collective power of other museum unions, we also hope to raise the standard for museum employees everywhere. Our successes can be used to the benefit of other institutions on their journey toward unionization.

Meredith Sellers is an artist and writer living and working in Philadelphia. She holds a BFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art and an MFA from the University of Pennsylvania. Conflating the centuries-old concept of the painting as a window with the infinite windows of the digital screen, her works utilize images appropriated from digital advertisements, stock photography, art history, and news media to examine systems of power and violence. Sellers has exhibited at Young Space, Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery at UArts, ICA Philadelphia, Lord Ludd, Take It Easy, Vox Populi, Icebox Project Space, and Pressure Club, among others. Her work has been featured in Art Papers, Maake Magazine, and White Column’s Curated Artist Registry. Curatorial projects include Chewing the Scenery at Crane Arts, The Midnight Sun at Pilot Projects (both co-curated with Jonathan Santoro), and Edith at Esther Klein Gallery. She is an editor for Philadelphia-based online art publication Title Magazine; her writing has appeared in publications including Hyperallergic, The Philadelphia Inquirer, ICA Philadelphia’s Notes, Pelican Bomb, ArtsJournal, and American Craft Magazine.