by Sam Mapp

Is art a game? A group exhibition titled Infinite Games, at High Tide, posits that it is. The title of the show refers to James Carse’s 1986 book, Finite and Infinite Games, in which he defines a finite game as one intended to be won, while an infinite game is played for its own sake. The Oxford English Dictionary defines the “infinite” as “without limit or end, boundless; immeasurable by no other than God, a transformation into mathematics.”[i] In other words, the infinite exceeds quantity and physicality to become divine. This metaphysical ambition, however, is tempered by the banality of a “game,” which means “amusement, sport,” and “fun.”[ii] Games are earthly diversions; we play them for entertainment. If art is an infinite, ongoing game, does it, in the process, become trite—or does it promise something more?

The notion that art is a game has provoked much of modernism. Marcel Duchamp employed a kind of gamesmanship throughout his career, strategically prodding the conventions of what art was as a way to imagine what else it could be. His exhaustion with painting led him to the readymade, which fundamentally altered the perception of art. No longer an object made by hand, the readymade promoted the concept of art—its ontological status—over and above virtuosity. The logic of Duchamp’s endgame concluded, appropriately—or ironically—with chess, a game in which he had long been interested, and ostensibly focused on toward the end of his life (in truth, during this time, he furtively made his magnum opus, the Étant donnés, 1946–1966). If his career began with the gaming of art, it appears to have ended with a more traditional distinction.

Many other artists, however, have openly delighted in the pretense that art is not only a game but one that will end. Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematist painting exhibition, the Last Futurist Exhibition of Painting 0.10, (1915), declared it just above the zero degree of art; succeeded shortly after by Alexander Rodchenko’s Pure Red Color, Pure Yellow Color, and Pure Blue Color (1921), that definitively claimed its end: “I affirmed: it’s all over. Basic colors. Every plane is a plane and there is to be no more representation.” But rather than a teleological conclusion, a search for purity and truth, what Malevich and Rodchenko failed to understand is that art is not finite but infinite; and that, surprisingly, there are infinities within its remaining vespers. Although Suprematist painting receded shortly thereafter, subsumed by Dada, Surrealism, and Abstract Expressionism, it reemerged as a potent force in the 1960s, catalyzing numerous inventions in three dominant formats: the monochrome, grid, and stripe. Minimalist sculpture contributed to this vocabulary of primary forms that activated the gallery space as more than neutral but, rather, “theatrical.”[iii] Insofar as either enterprise is an endgame—one that will become formally stagnant or indistinguishable from life—they continue, ad infinitum, in the present.

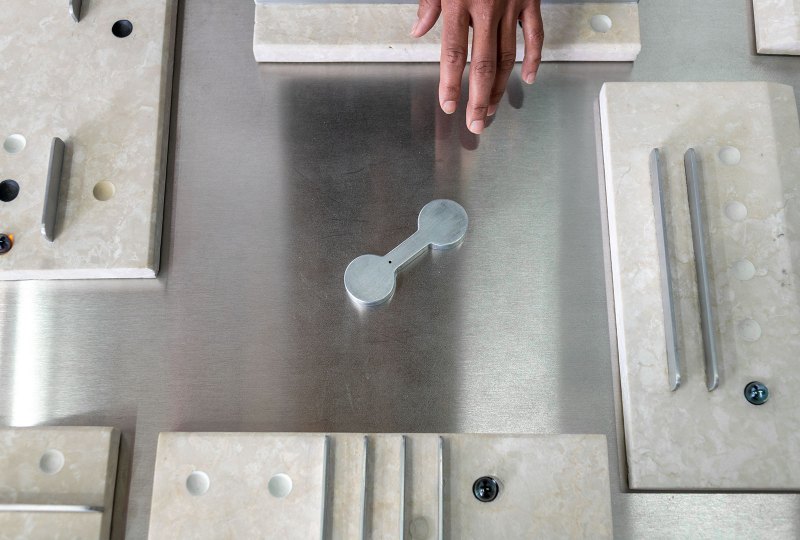

Alina Tenser, Elizabeth Atterbury, Micah Danges, and Jeff Williams are but the most recent contribution to this genealogy. Infinite Games, at High Tide, is a poetic exhibition of pictures, sculptures, and video that recycle vestiges of modernism in unexpected materials. Upon entering the gallery, Tenser’s Game Table sets the tone for the exhibition. A large stainless-steel tray sits flush on a folding table at a conventional height. The tray is filled with handheld sized shapes of marble with aluminum slats, finished cleanly, with ovoid indentations for marbles to rest. The composition of the objects in the tray suggests a provisional set of forms; their potential is realized when set in motion, as the accompanying video, Game With Son, demonstrates on the adjacent wall. The video shows a bird’s-eye view of the artist and her son playing an invented game that involves manipulating nine aluminum shapes in an aluminum tray filled with water. A soundtrack of water trickling into the tray and clanking aluminum reverberates against the present sounds of the game being played in the gallery. On opening night, seven or more kids (including two of my own) immediately understood the intention of Game Table, adjusting, pulling, shifting, dropping, trading, and sliding the objects across the tray. They played the “game” intuitively, manipulating a finite number of forms for an infinite number of moves.

If Tenser’s Game Table literalizes the metaphorical game of art, then the remaining three artists maintain the metaphor, using the strategic potential of a “game” to mobilize their respective formal priorities. Pivoting away from Game Table, you find Labor, one of Atterbury’s four paintings in the exhibition, hanging on the adjacent wall. It—and the others—are 23 x 19 inches and white, all but blending with the gallery wall. Made of plywood, glue, and mortar, each is rectangular, composed of numerous shapes that have been separately cut and reassembled. The surface is in relief, furrowed by patterns of combed mortar that recall raked sand in a Zen garden. Shape, shadow, and directional pattern delineate the monochromatic structure of each picture which collectively interpret the history of monochromatic painting as a metaphorical puzzle.

This history began with Malevich’s Suprematist Composition: White on White (1918), which shows a white square suspended, off-balance, within a larger off-white ground. At Black Mountain College, Robert Rauschenberg made his White Paintings (1951) which served—as John Cage once said—“as airports for shadows and dust. Mirrors of the air.”[iv] Robert Ryman further developed this zero degree problematic by exploring subtle variations of white paint and numerous material supports and attachments to the wall. In all instances, the notion of gesso as preparatory ground led to the development of the support as image. To this history, Atterbury contributes paintings not made of paint, but of mortar (a material used for binding masonry walls.) She uses this material as a metaphor for paint, providing novelty and critical distance from the endgame procedures of late modernity.

The center of the room is occupied by three of Williams’ sculptures. To the far end of the room is Cane/Chair/Cake which is, as the title suggests, an aluminum cane, chair, and cake pans welded together. Either found objects or readymades, the gesture of welding materially unifies the objects while maintaining their semiotic individuality. Toward the center of the room, two sculptures, Six and Truncated Slice occupy the floor. Knobby welding seams along the edges of the metal plates shape conical geometric forms that sit flat to the floor. The facets are flocked brown through a process of electrification that produces a plush surface that could be mistaken for furniture. To encourage this reading—or misreading—welded aluminum egg slicers adorn the top of Truncated Slice while six welded pipes rest on top of Six. Either specific objects or elaborate bases for insignificant objects, Williams’ sculptures delight in compositional ambiguity and material uniformity.

Micah Danges, Houndon 53, and Montañès 96, 2019, photo by Constance Mensh

Complementing these works are Danges’ pictures which are equally hard to categorize, neither paintings nor photographs exactly, but something between, approximately. In this way, they are most similar to Gerhard Richter and Kaja Silverman’s notion of a “photo painting” (a hybrid picture).[v] Three of Danges’ six pictures are made of acrylic, graphite and pigment ink on backing paper. In this body of work, he uses a copy machine to reorganize, filter, and build new images using color reproductions of art and architecture from a series of folios originally published in the 1960s. The resulting images are scanned, made into impression prints, hand-colored, and then suspended between two sections of highly reflective acrylic panels. These images are faint, light pastels and delicate graphite, blended into atmospheres of history with titles such as, Maestri del Colore and il Polalio, 61. Like an afterimage or a ghost, Danges’ pictures hover in a liminal zone—an effect enhanced by his unusual use of cut acrylic, subdividing the surface into two rectangles and one one-inch, lengthwise strip that refers to the binding of a book. As complete objects, these pictures engage the gallery in yet one more important way: when viewed from a distance or from an oblique angle, they mirror the gallery, other artworks, and viewers. The present circumstances of his picture are reflected in a history of faded figures and lost words. These are something like an impression of, or a memorial to the endgame.

Micah Danges, Maestri Del Colore, 243, 2019, photo by Constance Mensh

In art historian Carol Armstrong’s essay, “Painting Photography Painting, Timelines and Medium Specificities,” she argues for the irrelevance of endgame logic and concludes that the very nature of painting is not specific, but plural. The medium actually resists reduction by courting discursivity and hybridity, thereby gaining, not only from its own history but also from other arts and technologies to continuously reinvent itself. What appears, in Infinite Games, on first blush, to be motifs of aesthetic reduction—monochromatic pictures and minimalist sculpture—turn out to be objects that are more open and complex. “Here ends are not endgames, but re-beginnings.”[1]

Infinite Games is on view at High Tide from November 2–14, 2019.

Bio:

Sam Mapp is an artist and writer living and working in Philadelphia. He is currently a Ph.D. candidate in the History of Art at The University of Pennsylvania where he is writing about the congruence of pictures and architecture in contemporary art, a phenomenon he is calling “the pictorial area.”

www.sammapp.com

[i] Oxford English Dictionary Online, Accessed date: November 30th, 2019 https://www-oed-com.proxy.library.upenn.edu/view/Entry/95411?rskey=resz5b&result=1&isAdvanced=false#eid

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Michael Fried. “Art and Objecthood”. 1967

[iv] John Cage, The Charles Eliot Norton Lectures, in I-VI (Cambridge: Harvard, 1990), 26

[v] Kaja Silverman, Flesh of My Flesh, “Photography by Other Means”. (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009) 168-257.

[vi] Graw& Ewa Lajer-Burcharth, eds Painting Beyond Itself: The Medium in the Post-Medium Condition(Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2016):123–143.